DC, Almost

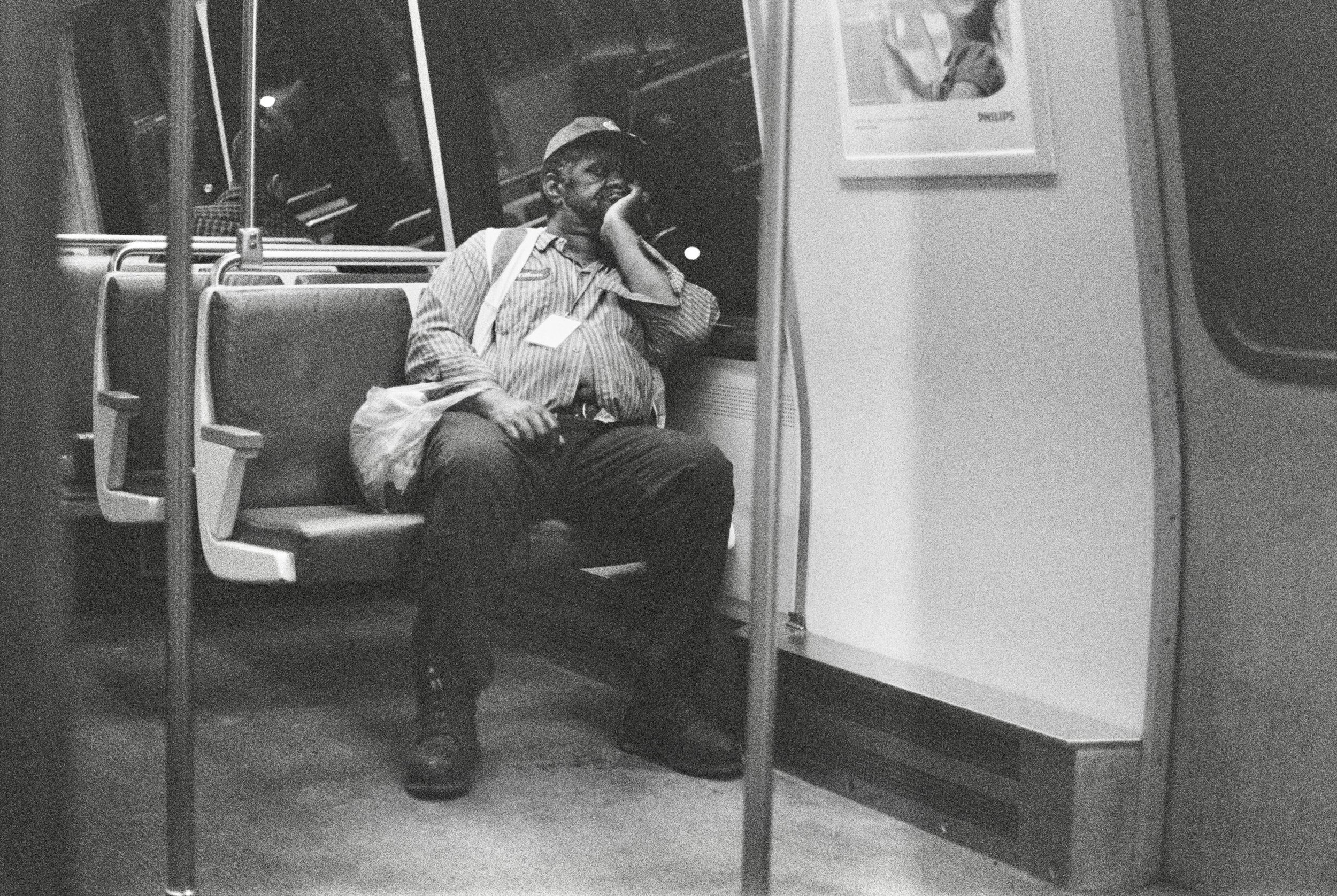

Lloyd Foster, Untitled, 2018

First, locate yourself.

Washington, D.C., modest in size and character, pools in the expanse of its most approximate suburbs. Diamond-shaped, its sharp corners aim toward the cardinal directions while its southwestern quarter tears off at the Potomac River, where water separates Maryland from Virginia.

Lloyd Foster, Untitled, 2018

Gripping the city by its northern tip, Montgomery County, Maryland lays like a mammoth slab resembling a rectangle in shape, while its similarly girthy neighbor Prince George’s County, Maryland curls around D.C.’s eastern point.

Tucked under the District’s southwestern tear, humbly sized Arlington County, Virginia nearly completes the diamond and, southwestward, Fairfax County, Virginia outsizes and surrounds it.

Chat of your visit to the nation’s capital, and all but residents of the city proper include these counties in its parameters. Besides this, each county garners its own distinction.

Lloyd Foster, Untitled, 2018

Montgomery County, Maryland has the largest population in the state, while Prince George’s County retains its reputation as D.C.’s Black Suburb. In Northern Virginia, Arlington and Fairfax Counties boast some of the highest average household incomes in the country. Farther out, however, counties gathered under the D.C. umbrella but lacking such prominence seem to vanish.

I want to take you where few tourists travel, past the allure of landmarks and monuments and into forests demolished for dreams of ownership. Drive 24 miles southwestward—take Interstate-395, then I-95, past Arlington and Fairfax Counties—and you’ll hit where I call home.

Prince William County, Virginia welcomes you. Woodbridge overlooks your arrival. This is a big suburb, not a small town.

Head south of here, and many central and southern Virginians express aversion toward Northern Virginia’s affluence and notability; they say it’s not Virginia, but D.C. North of here, many believe Woodbridge’s distance from the city excludes it from the metropolitan area; they say it’s Virginia.

Maybe it’s neither. Maybe it’s nowhere.

Lloyd Foster, Untitled, 2018

Woodbridge’s redeeming attribute: Potomac Mills outlet mall, one of the biggest outlet malls in the area. A high school friend once remarked that Woodbridge’s positioning beside the highway makes it feel like a giant pit stop on a roadtrip to somewhere else, and if it weren’t for Potomac Mills’s emblematic sign towering over I-95, this place would feel even less auspicious.

Keep driving, farther from the metropolis, and visibility dims with each mile. For those that must fight for the visibility that the more privileged acquire upon birth, this truth can prove even more isolating. But magnify the U.S. and find people inhabiting invisible places—places few mention or know of unless from them—and utilizing various tools for escape.

+++

A mastery of basic HTML coding, my father’s SLR camera, a laptop, a ride to and from Potomac Mills, a CD collection as mood board: My Chemical Romance, The Blood Brothers, Taking Back Sunday, Scary Kids Scaring Kids, Bring Me the Horizon, Coheed and Cambria. Apathy aestheticized as a posture and sensibility. A slouch, a head tilt, a pigeon-toed stance.

Lloyd Foster, Untitled, 2018

Middle school peers threw sharp words at the hips in my walk and the inflections in my voice, and at home, jokes amongst family on my dress and music taste deepened self-hatred. I belonged to nobody, and no label welcomed me. So, upon entering Woodbridge High School in 2006, aged 14, a transfer and unknown, I fashioned a new version of myself—one that veiled emotional pain under self-asserted gravitas. I was insecure, yes, but artful and strategic in concealing this truth. I championed clichés of teen rebellion through profanity, disregard for curfew, and occasional cigarette-smoking. I performed unbothered and, for the first time, I stood with others.

Unlike the contemporary hipster, we proclaimed our title with zeal. We were Scene Kids, and we populated food courts, concert venues, and web browsers. We took our name from the “scene”—small clubs and bars in nearby cities in which we’d gather to see popular screamo, metal, and alternative bands of the mid-aughts. And despite this title, our online identities proved most essential in maintaining relevance. We wanted friends as six-figure numbers we exhibited as evidence of clout. We wanted pic comments and wall comments. We wanted fame.

Lloyd Foster, Untitled, 2018

We stalked amongst peers, contemptuous of those unhip to irony masquerading as subversion. We rehearsed unaffectedness toward gore, adorning our Myspace profiles with imagery littered with innards and blood. And through this performed enjoyment of violence we interpreted the guttural roars produced by the vocalists we idolized.

We were sarcastic, elitist, and superficial by Urban Dictionary definition, dismissive of mainstream music, popular dress, and established etiquette, and proficient in makeup, social media, and deadpan vulgarity.

We wore skinny jeans, slip-on Vans, and Nike Dunks. Our band t-shirts fit tight, and we accessorized with thin elastic headbands, sweatbands, and bandanas rolled to a cuff. Most of us straightened and dyed our hair bright colors. Some teased ours for volume that narrowed as it hit the shoulder, adding elaborate clip-in extensions of neon and leopard print. Others styled slick bangs that swept across our foreheads. Many of us sported heavy eyeliner, piercings, and tattoos.

Lloyd Foster, Untitled, 2018

Bands played at venues in D.C., and throughout metro cars heading in from Northern Virginia you found us, scattered here and there, aware of each other but too committed to our personas to interact. And once in the city, we were oddities—white peers almost disruptive amongst black locals—and both demographics underscoring the empty space in which I resided. Maybe I was neither, maybe I was nothing.

Looking back, I recognize a burgeoning self-confidence that solidified upon moving to New York City after high school and meeting queer black peers. Hearing snippets of D.C.’s gay black history, I sometimes question whether this sense of self-worth could have formed earlier, but then I remember the distance between my suburban life, absorbed in the online, and the city that was just as near as it was far.

Regionally, is it even my history? Extended family members inhabit D.C., yes, but how can I claim a city when I was shaped by a place related to but remote from it?

My name is Justin Allen, and I am from Woodbridge, Virginia.

+++

DeWalden Jones, Jr. was born on March 23, 1959 to parents Sandra and DeWalden Sr. at Washington Hospital Center in Washington, D.C. He grew up in a residential neighborhood in Southeast, and attended Sousa Middle School where he ran track.

At H.D. Woodson High School in Northeast, he directed and sang in the school’s gospel choir and was nominated to office in the school’s first graduating class of 1977.

In 1983, he met a woman named Cathy. In 1987, they married.

In 1985, he fell ill, inciting frequent hospital visits. Despite this, he continued his choir work.

A member of Canaan Baptist Church, he sang in the Young People’s Choral Ensemble. With them, he toured cities throughout the southern United States, including Memphis, Houston, New Orleans, and Atlanta.

On May 5, 1995, after fighting his illness for over ten years, he passed. He was 36.

Thanksgiving 2014. DeWalden’s mother heads out of her home in Washington, D.C. with her husband George behind the wheel. Her three nephews, each of them in suburbs, exchange hosting responsibilities every year. This year, her nephew Jeffrey and his wife Jean, the only members of her extended family that live in Virginia, offer their home.

Lloyd Foster, Untitled, 2018

She and George arrive amongst other relatives and make their way up the driveway in their long coats and brimmed hats, a shuffle that characterizes the quaintness of this place—slow, discrete, the younger ushering the older.

“There’s DeWalden,” Sandra passes me a photo after dinner. I’ve seen pictures of him before, always with a smile. I imagine similarities between us based on stories and photos like this. I imagine a shy side to him, though all stories I know paint him as extroverted. I try to imagine the sound of his voice, too, never thinking to ask about it.

In my favorite photo of him, he poses in an off-white suit and brown dress shoes outside a relative’s house. Whose, I’m not sure, but my familiarity with the look of the residential neighborhoods makes D.C., and my cousin, feel closer.

I often imagine him walking to church, down a residential street, smiling in that suit.

We continue to pass old photos, our plates cleaned of the candied yams, collard greens, mac and cheese, honey-baked ham, and pie my mom made. We take new photos, the younger assisting the older with their smartphones. We remark on the football game playing as background sound until a fumble or foul occurs. We discuss since resolved family conflicts and laugh about them. My cousins and uncles from Prince George’s County mention movie theaters, malls, and restaurants they frequent, and my ignorance of these locations reinstates feelings of distance.

Then, as is common in suburbs, the gathering ends in measurable time. The goodbye is southern in pace, too polite for hurry and full of stalled conversation, but early. Relatives plate and foil what they couldn’t finish. My mom gathers coats from the closet, my father promises to chat with those not in attendance. The older lean on their canes and walkers, the younger usher, and they all shuffle out as they came in—through the front door, down the driveway, into their cars—and head back toward the city.

Lloyd Foster, Untitled, 2018

Publisher's Note: DIRT commissioned Lloyd Foster to pair photo landscapes with the author's essay in an effort to spearhead innovative collaborations between writers and artists.