Hyperlink Blues: Experiments in VR Psychotherapy

I'm sitting in an amalgam of Sigmund Freud's consulting office in Vienna and Sherlock Holmes' sitting room at 221B Baker Street.[1] Typically, I try to get here early, before my therapist enters the room in cartoon simulacra format. This gives me enough time to (emotionally) prepare for my session and acclimate to this environment since I arrived sans transportation or any other liminal spaces. All the while, I'm sitting in my bedroom, physically, in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, wearing pajamas and a VR headset.

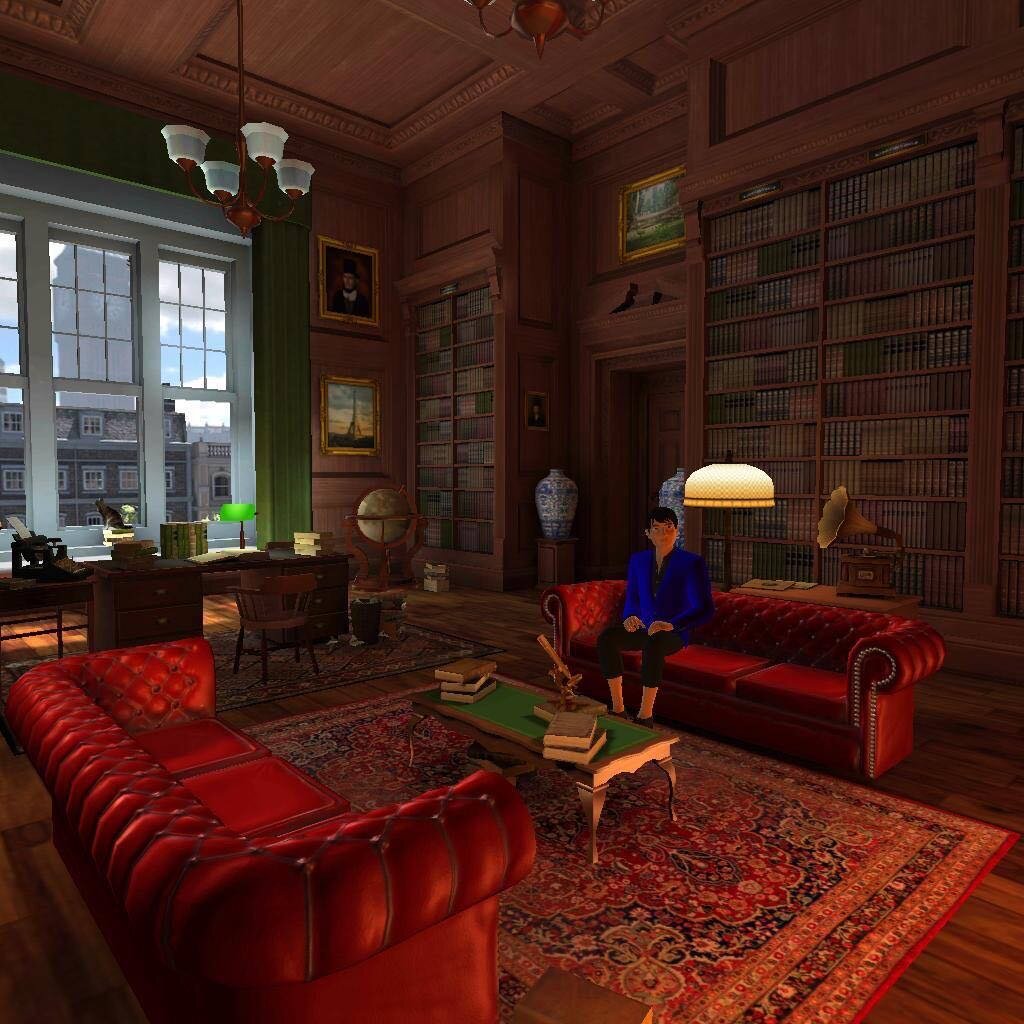

Despite the low-res kitschiness of this digital interior, I do find respite from being immersed in it. The fireplace is crackling endlessly (or at least until my battery runs out) and, behind me, I hear the sound of a grandfather clock, metronomically ticking away. On the window sill, there's a cat on loop— a nod to the déjà vu scene in The Matrix, perhaps—rotating its body every three-and-a-half seconds. As I look around, many of my critiques about the interior are surface-level—shaped by my training as an architect. For example, I have no affinity for the tongue-in-cheek British iconography and bourgeois velour. The Qashqai rug, however, can stay. But overly picking this environment apart might wane the illusion: the modern shaped couch with all-over tufting feels anachronistic, and shadows are misaligned with the window orientation.

A pop-up message interrupts my time digitally acclimating: my therapist would like to join me and begin our session. Their avatar renders slowly from the bottom up, emitting an electric purple aura, and for added spectacle, it rings with the cybernetic sound of a bootleg Star Wars Holocall. Already familiar with how my therapist looks like IRL, it's difficult not to laugh at their facsimile body in unremarkable resolution. I note my observations about the digital interior and the software's attempt towards realism via atmospheric stimuli—I can help lower their volume, my therapist responds.

This room is labeled "The Study," one of the several “destinations” available in this VR application. This is the default environment chosen by my therapist, but other ready-to-inhabit spaces on this platform range from a conference room in a skyscraper to a floating outer space environment. The software we’re using is vTime XR, a free-to-play virtual and augmented reality social network app. Its self-purported mission is to "transform social engagement through digital experiences that are as powerful as face-to-face interactions."[2]

If I look down I see that I'm wearing a digital copy of my favorite jacket, made of one-hundred percent baumwolle cotton in the vivid color of hyperlink blue. My therapist is curious why it was important to recreate my jacket, knowing it took a considerable amount of time in the avatar settings to craft a digital facsimile. I can remember putting it on for the first time in Los Angeles last summer during an escapade up the Pacific Coast Highway. That was a week after my break up and the morning after my cousin's memorial service, two events not unrelated. When I put on that jacket, I'm reminded of Maggie Nelson's Bluets: how one can hope to learn something about "the fundamental impermanence of all things"[3] by meditating on blue objects, waiting until the sun lifts away their hues.

My therapist had most of this information, as I described that Summer as a double-grief of some sort with no room to heal in my application to the William Alanson White Institute, an institution for training psychoanalysts and psychotherapists. The institute paired me with my therapist, and once back in New York City, I underwent analysis with them, IRL, three times a week.

Experimenting with VR psychotherapy was a personal inquiry that eventually became a necessity. When we met in person throughout the fall and winter, I would commute a two-and-a-half-hour round trip and traverse three New York City boroughs. The root of the word “travel” is indeed travail. Psychoanalysis doesn't begin and end during sessions—spilling over into the other parts of the day—and I preferred the displeasing commute over pushing an "On" button. Travel can absorb emotional spillover. Still, as the commute took a toll on my body, I arranged a permanent virtual set-up, knowing that my therapist was holding VR sessions with other patients. COVID was also inevitably on its way to New York City, and by March, we went virtual, just as seemingly everything else became digitized.

We shifted softly into our avatar bodies by using our headsets face-to-face. We began this transition on session forty-one. Still meeting IRL, we entered into our headsets[4], crossing over analog and digital. There was always a stage-setting and choreography to the analysis. I would arrive at their apartment-office, sign in with their desk clerk, take the elevator up to the 14th floor, and their door would always be slightly ajar. They never got up from their seat. A courteous Welcome with a nod followed, and their silence ensued.

The term my therapist uses for how they arrange the analysis is the frame. The frame is something that inevitably gets broken. Breaking the frame is perhaps part of therapy. Some of it might be enacted but its immediacy and immersive participation make it undoubtedly real. They sat on a green velvet couch, not dissimilar to Freud. (Though, we faced each other on our own sofas about eight feet apart.) Behind my chair was 1-to-1 wallpaper with an image of a forest with a plaster deer head. From their office, you overlook Long Island. I once asked why all their books were covered in white paper, and their response, hesitantly: an abstracted environment can allow oneself to project onto their background.

How are you? For the first time ever, one week into VR, my therapist asked me how I was doing. Was it the high emotions stirred by the pandemic? Or maybe they were compensating for their avatars' inability to show full presence? It's difficult to determine, but it was apparent that the quotidian IRL rituals that seemed mundane were only to be evident when absent, lost in VR space. The charged thickness in the air when two people share a room is lost in virtuality. Perhaps then digital environments require more intentional expressions.

Even in a space where seemingly everything can be conjured, there are limits. The only bodily agency over my avatar is in my head. That is, when I nod, my avatar nods. This captured movement goes a long way in making sure we're both on the same page, but it doesn't account for the rest of my bodily gestures. My avatar is set to perform pre-choreographed movements when I speak into the device. This is unlike the more widely known Freudian VR study, which gave the users full-body control in an attempt to create "a way of empowering someone and making them the protagonist of their life."[5] I once dreamt I was giving a five-minute standup routine about how sometimes my avatar's gestures are in sync with what I'm saying, but sometimes I'll share something depressing, and my avatar will indifferently point as if giving directions. In my dream, nobody laughed.

An analysis is what happens when two people share something intimate and don't have sex, my therapist once said to me half-jokingly. After about a month of VR together, we agreed that we have become more intimate in this digital space.[6] But as a designer and artist, I question how this arrangement could be different. What really is a space to be ‘suitably psychoanalyzed?’ How might an “Internet-Persona” voice a loud or quiet tone?[7] How can we use the internet the way we feel it should be used, with generous interfaces capable even of “love-inputs?”[8] How do we “reach across the chasm of seamless signal?”[9]

That isn’t to say there hasn’t always been room to experiment with the software interface. The week after I was asked if I would be interested in writing this piece, I decided to relocate to another ‘destination:’ Studio V. In a late-night talk show set up, there’s a camera operator in ready-position and a sold-out live audience (either entranced or in boredom). Why have therapy in front of an audience? my therapist asked, sitting next to me in the other studio guest chair. In learning to feel first and ask questions afterward, sometimes the body knows first and you need to give it space to find out.

As an analysand with a headset on, I sometimes feel like a character in Satoshi Kon's techno-thriller Paprika (2006), a film that explores the relationship between digital media and our perceptions of dreams and reality, how even the most minor of elements in our dreams can reveal our subconscious.[10]

A scientist by day and detective by night, Dr. Chiba, the main protagonist, is looking for the thief who stole a "DC Mini" prototype. Developed by Atsuko and her colleagues, this stolen apparatus allows psychotherapists to share dreams with their patients. The movie's plot develops as they learn how the device can cause psychosis in its victims if left in the wrong hands. Atsuko has been illegally using a DC Mini to help psychiatric patients outside of her research facility through the titular Paprika, Atsuko's more vibrant dreamworld alter-ego.

One such patient aided by Paprika is Detective Konakawa, who suffers from an unsolved homicide nightmare. In a scene where he unexpectedly meets with Paprika at http://www.radioclub.jp, she asks, Don't you think the Internet and dreams are very similar? They are both areas where the repressed conscious mind vents. There is an optimism about digital media that has been fruitful for thinking about my virtual experience. The film is an adaptation of a novel in 1993 and captured anticipation about technology and digital media: the novelty of experiencing anonymity and the chance to create your own reality. As Paprika states in the film, the Internet and dreams are the means of expressing the inhibitions of mankind.

VR environments can be particularly useful for discussing dreams. My therapist posits how the oneiric nature of the virtual can help with dream recall because of their visual similarities. Whether or not this statement is true, during the onset of VR therapy and quarantine, my dreams did come quickly to me. Many of my dreamscapes quickly turn haunted and ghastly. I began to identify with Detective Konakawa most, founding myself in what seemed to be an endless private investigation, repeatedly dreaming of my cousin's childhood home before they passed away. I question why I'm doing this in the first place: why relive and retell images of their suicide if I’m creating a space for care and healing?

Intimacy mediated by digital technology can feel contradictory. There is a small window of relief to speak of past trauma through an avatar—or, in other words, to be digitally eclipsed but still feel present. In an interview about Paprika, Satoshi Kon affirms that "people free themselves from their daily oppression" when "participating in chat rooms and Internet forums."[11] Like loose fingers on a keyboard when writing anonymously, inhibition is narrowed when mediated through pixels. That safety in online participation can create immediate digital intimacy amongst strangers on the internet and even trolls in the comments section.

At the same time I also have thoughts of my intimate data being sold back to me via Instagram-shopping-recommendations. Before working with Vtime XR, I had to compromise my privacy, consenting to terms like "We will never sell your information to third parties. However, like most other internet-based services, we use third-party service providers (such as Amazon Web Services and Google Analytics and Facebook)." I don't know what true digital intimacy looks like. Still, I do know it doesn't involve the product manager of the device you're wearing to be mining your data, and through this extraction, plotting to have your VR avatar set the foundation of your identity in the future.[12]

Therapy has become a space to be curious about how I relate to others and me. Or to borrow my therapist’s words from a previous session, using this relationship to make sense of other relationships. After three months of VR sessions, I felt I had upgraded my avatar by adding matching pants, completing a hyperlink blue suit. There's the part of you who could be vulnerable and afraid to be seen sometimes, and then there's the part of you who can wear a bold blue suit. Today it seems like we're talking about split-selves or fragmented selves… How can we make this a place where we can bring in all of Mark’s selves?

At the end of the film, Paprika has been captured and has her skin literally peeled away, revealing Dr. Chiba underneath. In a violent act of being seen by others, Atsuko neither accepts nor rejects Paprika as her true self, demonstrating that Paprika is one facet of her identity. Detective Toshimi concludes his investigation after synthesizing leading pieces from nightmares and the real. Both live in their jointly composed reality: bodies with avatars. Unlike a film, however, an analysis is messy and has no neat resolutions.

There are, apparently, glitches between my various selves—how I see myself versus how I’m seen, flickering between the two. Various identities—cultural, historical, sexual, and perhaps others—have been fragmented and refracted through each other. Have we found the hyperlink between your multiple selves? I have little desire to answer the question, as I don't see it necessary to sum up all parts of me. Instead, I side with Clarice Lispector's words: Parambolic as I am. I can't sum myself up because it's impossible to add up a chair and two apples. I'm a chair and two apples. And I don't add up.[13]

On our one-hundredth session, we met IRL, as I was leaving for grad school. There was that charged thickness in the room, and it seemed there was only more on the table now. A gooey intimacy with generous interfaces is possible, but it's only one more room to share and be curious in. Perhaps the first step of healing is acknowledging there's a space there, to begin with.

Notes

1. I verified the design intent of “The Study” after tweeting a screen capture and tagging the app. Art Director Obi @kokotoni on twitter commented: “You're spot on with those references. Both were major influences to our team's environment creation and texture generation. Hope you felt suitably psychoanalysed!”

2. vTime Limited, “VTime - Reality Reimagined,” December 22, 2015

3. Maggie Nelson. Bluets. 2009, 82

4. We’re using an Oculus Go 64GB, Standalone Virtual Reality Headset (no longer in production)

5. Sofia Adelaide Osimo, Rodrigo Pizarro, Bernhard Spanlang & Mel Slate, Conversations between self and self as Sigmund Freud—A virtual body ownership paradigm for self counseling. Scientific Reports - Nature. September 10 2015

6. We agreed that it is difficult to isolate what VR afforded as a tool to relate with and what ran parallel to our experiment, the vulnerability in a pandemic and the peaking protests against the assault on Black lives.

7. Mindy Seu, Mindy Seu on Making the Things You Want to See, The Creative Independent, January 30, 2018

8. See The Life and Death of an Internet Onion by Laurel Schwulst, 2020

9. Fei Liu, A Drop of Love in the Cloud, The Creative Independent, April 4, 2018

10. Kazuo Horiuchi, The Making of Paprika, 2007

11. "Paprika: Interview with Satoshi Kon." Interview by Romain Le Vern. DVDrama. Excessif.com. Web. 02 Oct. 2010.

12. Janus Rose, “The Dark Side of VR: Virtual Reality Allows the Most Detailed, Intimate Digital Surveillance Yet,” The Intercept, December 23, 2016

13. Clarice Lispector. Água Viva. 1973, 67

Mark Anthony Hernandez Motaghy is an artist, architect, and organizer. They are a research candidate at MIT, investigating network infrastructures, informal economies, and the politics of care. Mark is one-half of the collaborative spatial practice If So Then.