Embodying the Archive

A simple Google search for the word “archive” results in countless images of temperature-controlled facilities with rows of boxes containing old documents, books, photographs, and objects. What we define as an archive is shaped by several factors: dominant cultural ideologies, what society deems valuable/worth recording, and the ways in which we seek knowledge. With this in mind, my intention here is to “queer” the archive;[i] to consider other spaces and places in which the archive resides. How can we re-conceptualize and challenge the archive by shifting our focus from objects to bodies?

With this in mind, I turn to drag and ball culture as an example of history told through bodies, rather than objects. Though in existence for more than five decades, the largely white, middle-class, heterosexual world was first introduced to the underground ballroom culture through Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning and Madonna’s 1990 music video Vogue. These depictions, it must be noted, are singular in their representation of the body as simply spectacle. Drag and the ball scene undoubtedly revel in the art of spectacle; however, at their core they serve as sites of both resistance and self-preservation, not simply dance parties and performances. Marlon Bailey in his monograph Butch Queen Up In Pumps writes, “this community offers an enduring social sanctuary for those who have been rejected by and marginalized within their families of origin, religious institutions, and society at large. For most, the Ballroom scene becomes a necessary refuge and a space in which to share and acquire skills that help black and latino/a LGBT individuals survive.”[ii]

Thus, the process through which the history of the ball scene and drag culture is archived is, in a way, antithetical to institutionalized archiving. For the sake of brevity, I will elucidate two such archival strategies: a perpetually lived and shared archive, and a repeatedly performed and spoken archive.[iii]

Ball culture and drag are lived and shared through non-normative networks of kinship. Ball houses -- for example the House of Mizrahi, the House of Ninja, the House of Xtravaganza, the House of Aviance, the House of Labeija, amongst countless others -- and drag families -- which include drag mothers, daughters, and sisters -- form genealogical networks of information sharing, support, longevity, and memory. House members and drag families maintain a sense of their identity and history by “taking on” the name of the house or family they belong to (though not always). To consider oneself a part of a ball house or drag family is to take on the responsibility of carrying the torch, continuing the legacy, and ensuring longevity. During the height of the AIDS crisis, ball houses supported their most vulnerable members by providing housing, food, covering healthcare costs, and offering emotional support. Additionally, these kinship networks served as lines of communication for sex education and the latest on AIDS treatment and prevention.[iv] Due to the United States’s unilateral negligence of the crisis, and particularly its impact on LGBT black and latino/a communities, many houses were left to formulate prevention and treatment strategies on their own.

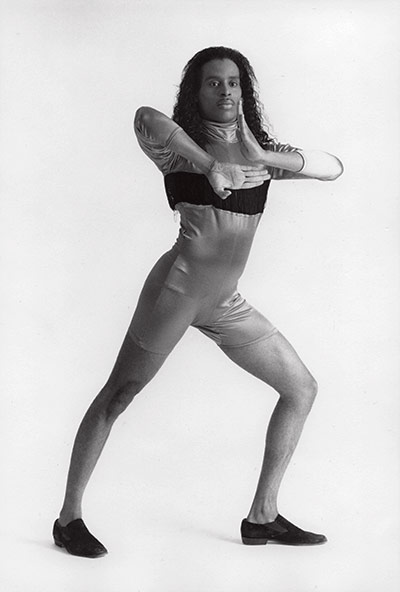

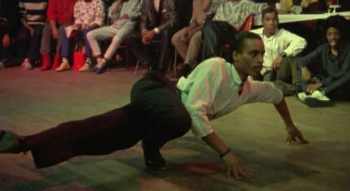

(L) Chantal Regnault's photograph of Willi Ninja; (R) Willi Ninja in Paris is Burning

Additionally, in terms of ballroom culture, official titles and prefixes serve as records to one’s own experience and history within the ball scene, and as a system of classification. The status of “legendary” or “icon” is bestowed upon members and their houses, which denotes years of experience, prestige, and solidifies, in a way, the memory of an individual or house.

The second strategy, the archive as spoken and performed, arises within the actual balls and drag performances. The archive is activated through ritualized gestures, song, dance, movement, lip-synching, and performance. Each ball is a re-telling, of sorts, of the history of ball culture. Take for example Willi Ninja, the “godfather of voguing” and previous mother of the House of Ninja (he passed away due to AIDS-related heart failure in 2006), whose style of voguing is iconic. To mimic Ninja’s egyptian, hieroglyphic-like movements is a commemoration and re-telling of the roots of vogue.

Drag performances, both mainstream and underground, serve as sites of memory where through performance and song the history of drag is repeated over and over again. We can think of any number of drag impersonators or drag queen’s whose aesthetic and performance is rooted in the history of gender nonconformity and gender-bending. Pussy Noir, an androgynous performer and entity of the DC nightlife circuit and native Washingtonian, spoke of his belief that the body stores and expels energy, and that this kinetic energy is carried through and often a driving force for his performances. Through his gestures and movements he “blends both the elegant and melodic as well as the wild and seductive.”[v] The body, as an archive, stores, maintains, and when called upon, re-tells its history.

Images courtesy of Pussy Noir

I do not mean to suggest that the history of ball culture and drag are ignored within the archives. As early as the 1970s, LGBT-specific archives arose from the seeds planted by the culture wars -- including ONE Archives Foundation, Trans Archives, and The Lesbian Herstory Archives. In the age of social media, Instagram-based archives, such as the AIDS Memorial and LGBT History, have also come into existence. Artists such as Rashaad Newsome and Kia Labeija are examples of the interrelated history of the art world and drag/ball culture. Newsome, in recent years, has hosted the “King of Arms Art Ball,” a live performance event that brings together renowned figures from the art, fashion, music, literary, activism and underground LGBTQ & GNC vogue community.

While Bailey characterizes the ballroom scene and houses as sites of resistance and survival, I add that drag and house ball culture also serve as sites of self-preservation and memory. The archival strategies of drag and ball culture, while certainly not new to its members, offer exciting perspectives on how we can challenge the object-centric narrative of the archive and begin to embrace alternative archival processes.

-----

[i] Admittedly, the contemporary use of the term “queer” is almost meaningless. Nonetheless, to “queer” the archive, I am attempting to conceptualize it beyond its institutionalized, heteronormative, object-centric narrative.

[ii] Marlon Bailey, Butch Queen Up In Pumps: Gender, Performance, and Ballroom Culture in Detroit, (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2013), 6-7.

[iii] These two strategies are simply the tip of the iceberg in terms of theorizing drag and ball culture’s long and colorful histories.

[iv] It was not uncommon for members of houses or drag families to also serve in community-based organizations that formed to fight the HIV/AIDS crisis.

[v] Jason Barnes, e-mail message to author, September 27, 2017.

“Dissecting the Archive” is a seven-part piece commissioned by Common Field for the 2017 Field Perspectives as part of the Annual Convening in LA. Read all seven pieces here.