Fraught Empathy: Privilege & White Guilt in Contemporary Portraiture

Conversations around representation, identity politics and privilege are difficult and tedious — at times unproductive, at times fulfilling. DIRT’s mission is and always will be to promote critical dialogue within arts criticism and specifically within the DC arts ecosystem. It is a disservice to the DC community when we fail to critically engage work, particularly bodies of work that attempt to address (or redress) inequality.

----------------------

Whiteness is a state of mind: more than just race, more than just a physical body. It is a value system that organizes and designs hierarchies of gender, class, sexuality, and race. Historically, when white artists have looked to create work that attempts to cover topics of race, racism or systems of oppression, they focus the lens on marginalized communities. They often impose a voyeuristic gaze, rather than critically examining the role of whiteness and one’s own culpability within these systems of oppression. Frequently seen in the work of portrait photography, this gaze is coupled with an acknowledgment or admission of the artist’s privilege, while operating under the guise of ‘employing empathy.’ What does it mean to document a marginalized community that you do not identify with? Is it enough to simply acknowledge white privilege? Empathy is not immune to the pressures of inequality.

In many ways, we are socialized to believe that empathy is a good thing. Empathy is the feeling that you understand and share another person's experiences and emotions. It is the ability to 'put yourself in someone else's shoes.’ It can be an impactful form of human connection. But, empathy does not exist within a vacuum. It operates within systems of privilege and oppression. As Maggie Caygill and Pavitra Sundar, authors of the essay “Empathy and Antiracist Feminist Coalitional Politics,” explain, “the oppressed do not and cannot empathize with the lot of the privileged. It seems clear then that, like sympathy, empathy too relies on and reinforces a top-down power dynamic.” The authors go on to state: “empathy does not just draw parallels; it equates two vastly different situations. In the process, the experience and feelings of the ‘other’ are diminished or erased (yet again). What remains in focus is the pain of the privileged individual. Empathy thus repeats those same colonizing and totalizing gestures that feminist politics seeks to disavow.” Despite best intentions, these factors cannot be ignored when conceptualizing or employing empathy in works of art. This type of misplaced empathy can often be seen in contemporary portraiture from privileged white artists who seek to document and examine marginalized communities and stories that are not their own (the Whitney Biennial controversy of 2017 immediately comes to mind). The unfortunate lack of self-criticality beyond announcing privilege betrays these artists’ desire to participate in conversations on inequality since there is no direct attention to the issue they are most familiar with: their own white identities and community dynamics.

“the oppressed do not and cannot empathize with the lot of the privileged."

Two recent exhibitions —Kate Warren’s Banshees & Queens at the W Hotel, Washington DC, and Sally Mann’s A Thousand Crossings at the National Gallery of Art (NGA)—highlight how empathy is often used (and misused) in contemporary portraiture.

Banshees & Queens, a photography exhibition by DC-based artist Kate Warren, opened to the public at the W on Thursday, March 28 and was curated by Nina O’Neil (Monochrome Collective founder and previous employee of the National Gallery exhibitions department). “The show is an effort to use my privilege to amplify voices,” Warren states in her invitation to the opening reception, an event co-hosted by gallery and consulting firm Artist’s Proof.

“The show is an effort to use my privilege to amplify voices”

Image: Kate Warren's Banshees & Queens, on view at the W Hotel

Similar in their formalism, yet distinctly different in their content and execution, Warren displays two bodies of photographic work: Banshees (2016–2018), a series of hyper-sexualized women (both female-presenting and identifying) posing in intentionally “aggressive” poses mimicking the gaze of ‘street harassers’; and Queens (2018), which consists of “anthropological” photographs of DC ball and drag performers in “gender-bending” and “identity-based” performances. Presented intermixed throughout the two rooms of the lobby and dining room of the downtown hotel, these series aim to “investigate gender as a performative construct and create a sense of discomfort in the viewer that encourages reflections on those feelings” from which Warren believes that viewers will “proactively engage in the discourse on diversity.”

While both the Queens and the Banshees series are visually striking, after speaking with Warren directly, it became overwhelmingly obvious that one was conceptually stronger than the other for a number of reasons—the most glaring of which is time. In stark contrast to the two years spent developing the Banshees series, Warren was not shy about admitting that images shown in the Queens series were developed over the span of two weeks leading up to the exhibition (documenting a total of four events). While this timeline is not unusual for Warren’s editorial photo background, a body of work that claims to be an “anthropological” look at a community of which she is not a part of, desperately requires more time and research for it to operate as an accurate portrayal of the subjects beyond surface level. (The photographer’s intent to follow an “anthropological” method is also questionable considering that anthropology’s fraught history of photography and colonization is itself deeply tied to a voyeuristic gaze and the desire to understand and undermine “the other.”) If anthropological significance is the goal of these series, it inevitably suggests that Warren considers herself an expert on the culture she documents.

“The core of my practice is establishing shared vulnerability as a mechanism for building empathy, because that is ultimately what I hope to achieve,” Warren states. Though it seems plausible that through empathy she has instead shielded herself from partaking in any real vulnerability—a tendency she admits is not unlikely: “I struggle with being vulnerable with people because I’m from New England and sort of culturally we are pretty closed off from our emotions,” Warren says. “This practice is not about me, it's my way of processing, using the outside world to process questions I have about my own privilege and why I am the way that I am...I’m an upper-middle-class white chick and I'm not afraid to say it...if I don't identify my privilege, other people are going to be talking about it and I would like to be part of that conversation.”

Identifying privilege and examining it are very different actions. Acknowledging privilege is a great first step, but it shouldn’t be the last.

Image: Kate Warren, We're All Born Naked, 2017.

Identifying privilege and examining it are very different actions. Acknowledging privilege is a great first step, but it shouldn’t be the last. In many ways, the proclamation actively strengthens privilege underneath a mask of good intent in order to avoid direct criticism. The best defense is a strong offense—if you say it first, then, in theory, you protect yourself from someone else calling you out on it. As writer Fredrik deBoer explains, “like so much else in our society, the practice [of acknowledging your own privilege] has ultimately worked not to undermine structural racism—the putative aim—but merely to deepen the self-regard of the educated white elite…The unspoken but unmistakable logic is that by declaring themselves a part of the problem, they are defining themselves as part of the solution.”

"many yuppie-looking, straight-acting, pushy, predominantly white folks in the audience were there because the film [Paris is Burning] in no way interrogates ‘whiteness,’”

While Warren insists that the images reflected in the Queens series are not “about her” as the photographer, her voyeuristic gaze and authorship are undeniably present. Taking a closer look at the famed 1991 Jennie Livingston documentary Paris is Burning, an admitted inspiration to Warren’s series, might have served as an educational warning. Critics, including feminist icon bell hooks, have questioned Livingston (a middle-class, white, genderqueer lesbian) and her role as an enabler of cultural appropriation: “Watching Paris is Burning, I began to think that the many yuppie-looking, straight-acting, pushy, predominantly white folks in the audience were there because the film in no way interrogates ‘whiteness,’” hooks states in her 1992 essay Is Paris Burning?. “Jennie Livingston approaches her subject matter as an outsider looking in. Since her presence as white woman/lesbian filmmaker is ‘absent’ from Paris is Burning, it is easy for viewers to imagine that they are watching an ethnographic film documenting the life of black gay ‘natives’ and not recognize that they are watching a work shaped and formed by a perspective and standpoint specific to Livingston.”

“They love it. I wanted the space to be accessible and that it was for them, and that definitely happened.”

Image: Kate Warren, One Creates Oneself, 2017

In sharing that she gained access to DC’s drag and queer performance community through pre-existing relationships with key individuals who acted as “gatekeepers,” Warren shared that “people were really receptive and super glad to have me there and to have an opportunity to collaborate on something.” Adamantly confirming that she was completely candid about her project and her intentions with all those who posed for her camera, Warren shys away from calling anyone her “subjects”: “I treated them as collaborators and not as subjects (I wouldn't call any of these people subjects—because that seems like I am imposing my practice upon them instead of there being a robust back and forth).” When asked how Warren’s “collaborators” felt about their likeness being displayed on the walls of the W, she states: “They love it. I wanted the space to be accessible and that it was for them, and that definitely happened.”

"It’s all very ‘fierce fierce fierce, are you gagging yet?’ ... All under the niceties of shedding light, visibility, diversity, fucking the patriarchy, insert favorite buzzword/phrase here ___.”

Image: Kate Warren, Dive, Turn, Work, 2017

DC-based drag performer and co-organizer of the monthly queer performing arts event, Tea@TenTigers, Vita Santa Mamita (shown above at right) sees things a bit differently: “I provided consent, but all I was told is that Kate and Pussy [Noir] were working on a project together. I was not informed that the portrait would be sold for $4,200 in a gallery in a very public, touristy hotel and I was also never told the full concept behind the project. If I had more information, I would have likely declined to be photographed.” While Santa Mamita applauds Warren in some ways for wanting to do a project that celebrates queer, gender-nonconforming and transgender people, many factors surrounding the exhibit cause him to question Warren’s understanding of these communities and how they live: “Ultimately, the exhibit leaves me in a similar place as when I watch Paris is Burning. Visibility is great, but it bothers me that Warren (and/or the art galleries that supported/sponsored/featured this work) are able to capitalize on non-normative bodies without any publicly-stated intention of sharing that wealth, nor to make any visibly concerted effort in trying to humanize, empathize with, understand, or legit just have a real conversation with, members of these communities. Rather, it’s all very ‘fierce fierce fierce, are you gagging yet?’ and is able to be neatly packaged to a presumably rich, white, straight, cis person’s mantle as a token of cultural currency in 2018 hipster America. All under the niceties of shedding light, visibility, diversity, fucking the patriarchy, insert favorite buzzword/phrase here ___.”

Kunj, a co-organizer of Tea@TenTigers and DC-based performance/drag artist, headquartered at Trade Bar DC, shares in Santa Mamita’s comments on voyeurism: “The photo-series is very voyeuristic. Her approach and statements about the concept of the show seem very exploitative and not beneficial for visibility of, or directly to the queer (drag) community in DC. It actually does not sit well for me -- it feels like multiple steps backward in artistic activism and photojournalism. The fetishism of minority groups by predominantly white photographers is so played out.”

Objectifying culture undeniably disenfranchises people, especially when appropriating someone else’s cultural practice for profit. The result is a commodification of empathy, especially if the group drawn from doesn't see any profit from it. The potential for impact certainly goes beyond the surface-level interest of the Queens series in helping marginalized communities as Santa Mamita suggests: “I strongly believe Warren and/or the galleries should donate a certain percentage of proceeds from the exhibit to a local queer/trans support organization, such as Casa Ruby.” Unfortunately, the photographer only seems to be interested in voyeurism-as-visibility, resulting in a body of work that functions as an illusion of solidarity. As Susan Sontag insists in On Photography: “photography has become one of the principal devices for experiencing something, for giving an appearance of participation.”

Warren is by no means the first or the last white artist to delve into the murky waters of empathy, representation, and privilege. Sally Mann throws her hat into the ring in her latest exhibition, A Thousand Crossings, on view at the National Gallery of Art through May 28. The first survey of Mann’s work presented by any major museum, the exhibition is divided into five thematic sections: Family, The Land, Last Measure, Abide with Me, and What Remains. Tracking the evolution of the artist and her subject matter throughout the years, the show features work that tackles American history, identity, religion, and—most notably within the Abide With Me section, and particularly her Men (2006–15) series—race.

"The way the South was back in the 50s and 60s, I didn't know or even really see men of color,” Mann states, “yet we were all part of the same fraught, complicated place. So, these pictures are a very personal exploration for me.”

Image: Sally Mann, Men, Ronald, gelatin silver print

Through the Men series, an “introspective” portrait series of black men, Mann attempts to work through her own family’s history of slavery and racism and her own experience being raised by a black female nanny, Gee-Gee. Mann strives to “find out who those black men were that I encountered in my childhood, men that I never really saw, never really knew, except through Gee-Gee's eyes or the perspective of a racist society.” In her 2015 memoir Hold Still, Mann writes: “it's an odd endeavor, and the remarkable thing is that my models are willing to let me try.”

Mann drew inspiration from the work of noted artistic director, choreographer, and dancer Bill T. Jones, and his 2009 performance, Fondly Do We Hope...Fervently Do we Pray. In it, Jones attempted to reconcile his boyhood view of Lincoln during the civil rights struggle and as a mid-life liberal artist - using Lincoln “as a mirror through which we look darkly at ourselves." In a short documentary film featured within the exhibition, Mann explains that she recognized a shared interest in confronting difficult history through their art: “The way the South was back in the 50s and 60s, I didn't know or even really see men of color,” Mann states, “yet we were all part of the same fraught, complicated place. So, these pictures are a very personal exploration for me.”

Image: Sally Mann, Candy Cigarette, 1989, gelatin silver print

Depicting semi-abstracted black men who are asked to stand in for the thousands she never acknowledged, the Men series is a sudden and sharp turn from her previous depictions of family members in intimately private spaces on their property in rural Virginia, rural landscape photographs of the South, and visceral self-portraits.

"the camera's lens like a pair of eyes boring into their backs, the shape of their calves, the rise of their chests—she tries to confront the ghosts of those that lived on her periphery"

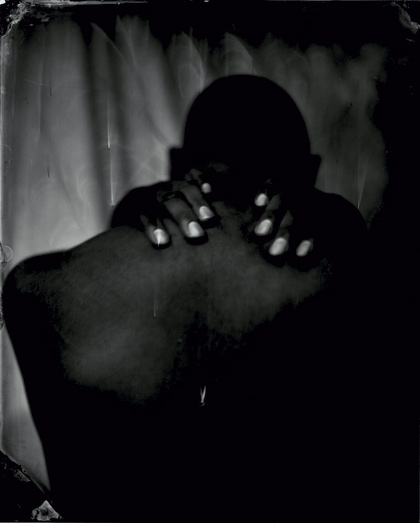

Image: Sally Mann, Men, Stephen, 2006-2015, gelatin silver print

While Mann’s Immediate Family work drew intense scrutiny focused on childhood innocence and exploitation, the series of her white family is most often viewed through a racially neutral lens. Illustrating relationships between childhood, adulthood, motherhood, gender, sexuality and coming-of-age, for Mann and her critics, the series did not explicitly intend to represent whiteness. Yet, when Mann wants to address her own family’s troubled history with race and identity, these black male models, “Lexington-area law students, kitchen workers or laborers” as stated in the exhibition catalogue, are asked to shoulder the weight of generations of black male identity in order to reconcile her own relationship to race.

Though Mann has not been immune to controversy in the past, critics have almost unanimously praised this most recent exhibition. Treading ever so lightly around the artist's depictions of race, critics like James Gibbons of Hyperallergic, barely skim the surface on Mann's fraught intentions, stating : "How well Mann navigates these choppy waters is ultimately up to each viewer to judge. I tend to trust her historical awareness and her depth of feeling". [Gibbons' unfortunate word choice here is packed with it's own history of trusting white southern women]

Instead of looking back towards her own family’s racist past, Mann chooses to take the path of using black male subjects as a cathartic tool, protecting her white Southern identity from self-examination. As writer Lauren Hansen puts it in the essay Sally Mann’s ghosts published in The Week: “Mann uses these men as a bridge to the past. Posing them voyeuristically—the camera's lens like a pair of eyes boring into their backs, the shape of their calves, the rise of their chests—she tries to confront the ghosts of those that lived on her periphery.” However, rather than directly confronting the “ghosts” of discrimination and violence, these photographs tow the line of trauma-porn and exploitation.

"[Mann] is keenly aware that the representation of African American men by white artists has a long and troubled history, riddled with dehumanizing and exploitative stereotypes and objectification"

Image: Sally Mann, Untitled

Like Warren, Mann’s privilege is acknowledged, almost acting as a disclaimer, freeing her of any further scrutiny. In curator Sarah Greenough’s exhibition catalogue introduction she writes, “Mann realized that these photographs were a fraught undertaking, not only because of the intimacy she hoped to establish, but also because she was a privileged white southern woman gazing at an African American man. She knows that in this highly charged time the larger question of who has the moral authority to speak about the atrocities and experience of slavery is a fiercely contested issue. And she is keenly aware that the representation of African American men by white artists has a long and troubled history, riddled with dehumanizing and exploitative stereotypes and objectification.” More or less stating, I know, and if I acknowledge I know, then I can do it anyway.

“Why do white artists think the only way you can discuss race is through the suffering of people of color?"

White artists have the unique power to dismantle white supremacy from the inside, organize their own, and have the hard discussion with friends, family and collaborators. As Maurice Berger writes in The New York Times, “in this regard, the very culture that excludes people of color, perpetuates racism and underwrites white privilege, can also alter racial perceptions by demonstrating the value of white self-inquiry. Yet such examinations remain extremely rare. Indeed, in American culture, the vast majority of important work about race is created by artists of color.” As Ryan Wong’s “A Syllabus for Making Work About Race as a White Artist in America” precisely states: “Why do white artists think the only way you can discuss race is through the suffering of people of color?” There tends to be more of a focus on the corporeal repercussions of oppression and violence, versus the origin of such oppression and violence. It’s the difference between treating the symptom versus the source.

While it is important to acknowledge privilege, this is not where one should stop digging; that is just the beginning. If one of the goals, as Warren has stated, is to make audiences “uncomfortable,” one must first ask who the audience is. If it is a conservative white majority, wouldn’t an investigation into their own white identities make them feel more uncomfortable than a voyeuristic look into someone’s else's?

“I feel like I just started this, and there are parts that I want to do deeper dives on,” explains Warren, who plans to keep documenting the drag and ball community in DC, exhibit the show in larger venues, and develop a documentary film to further explore the community. Though Warren has started to leverage some of her privilege and access for amplifying voices, hosting members of the drag and ball community on her podcast Insert Here, both she and Mann still seem to lack a full understanding of their power as photographers to access their conservative white counterparts.

Dismantling and facing white privilege requires self-reflection and time.

Reflection on one’s own family and whiteness is “hard” because it is intimately critical.

Both Mann and Warren have the capacity and skill to examine the complexities of their whiteness, white audiences, and white complacency. Instead, they choose to utilize their camera lens to objectify others in the name of empathy. This practice, as shown, reveals a form of sublimation in which a person copes with deep-seeded anxieties by stepping outside themselves, while pushing their own white self-inquiry and systemic complacency into the background. When asked why she wouldn’t consider turning the lens inward, Warren responded: “That’s hard. I would love to, but I also have a pretty decent relationship with my family...I am really taking the long game with them understanding what I do and why I do it and for me that means walking the walk on my values and leading by example.”

Dismantling and facing white privilege requires self-reflection and time. Reflection on one’s own family and whiteness is “hard” because it is intimately critical. If creating a piece that explores someone else’s identity feels easy, then it’s time to take a step back and reevaluate the body of work. The practice of co-opting marginalized narratives, perspectives, and bodies is at the core of white artists actively avoiding their own history in their attempts to engage in political conversations on identity. To successfully participate in these dialogues, it is essential to have more white artists making work that redresses inequality by directly confronting whiteness. Voyeurism in the name of visibility will always undermine the voice of the subject.