King of the Road

My love, give me my heart back. I ask you this kindly." Image by Muheb Esmat

It feels distant, but it was less than two decades ago that Kabul was a city with more pedestrians and bicycles than cars. A due consequence of prior decades of war and economic sanctions that were eventually lifted upon the beginning of the American invasion. At least for my family, it was a luxury to travel in cars. A luxury often regrettable if it was a long-distance trip, as the unfamiliarity will soon turn into motion sickness and everything that comes after. Even then, whether it was the old battered Russian Volgaos or the second-hand Toyotas, they always had a touch of localness to them. The insides of these vehicles were exuberantly decorated with postcards of flowers and Bollywood stars wrapped with see-through plastic to protect them from dust and the passengers' keen love for beauty. Beaded decorations dancing off the rear-view mirror and colorfully vibrant cloths covering the switchboard seats, all signs of taste (سلیقه) and marks of domesticating foreign objects as our own.

Energetic colors and alluring designs are hallmarks of Afghan culture. Their marriage with foreign-produced objects and material leads to a distinct hybrid culture bordering the local and the foreign. One of the most widely celebrated examples that have been around for at least half a century is the magnificently painted trucks. Adorned in painted flowers, roaring lions, serene landscapes, and rural scenes of Europe extracted out of postcards, they are artworks on wheels. Amid the visual spectacles of exuberant colors and mesmerizing shapes are texts to keep away the evil eye, wishes for a safe trip on the tortuous roads ahead, or couplets of love; a potion drunk by many.

In Afghan culture, poetry's place as the voice of the people and the powers dates back to millennia. The tradition's peaks are by the giants of Persian and Pashto poetry that include Rumi, Ferdowsi, Rahman Baba, Hakim Sanai, Makhfi Badakhsi, and many more. But roots and value of poetry expanded beyond master poets and collections confined to the boundaries of written manuscripts. Chaharbaitis and Landays are two short-form poems popular in the country's oral literary tradition. They constitute a language of expression and knowledge passed down for generations and have found new shapes and meanings at different times and contexts.

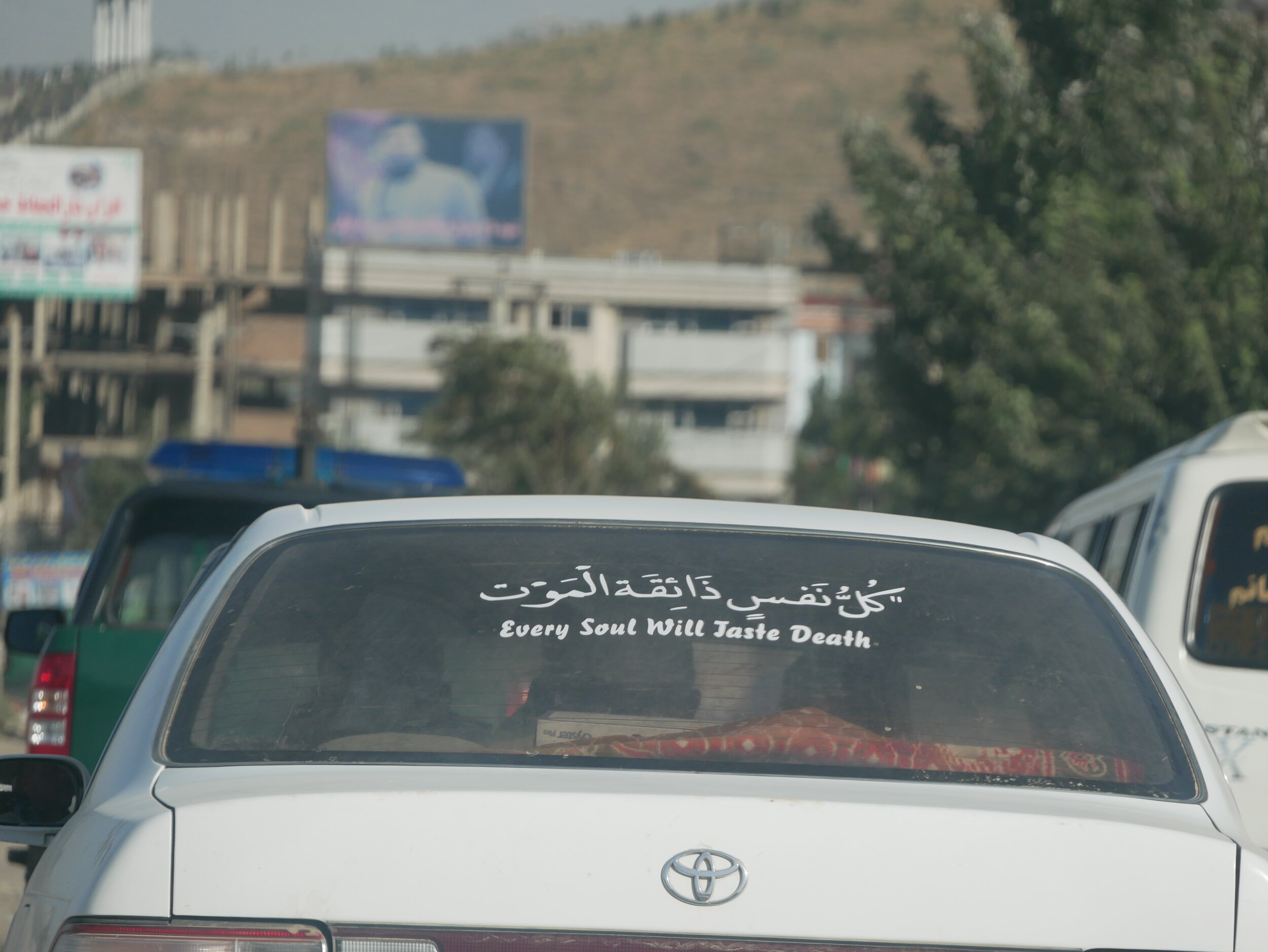

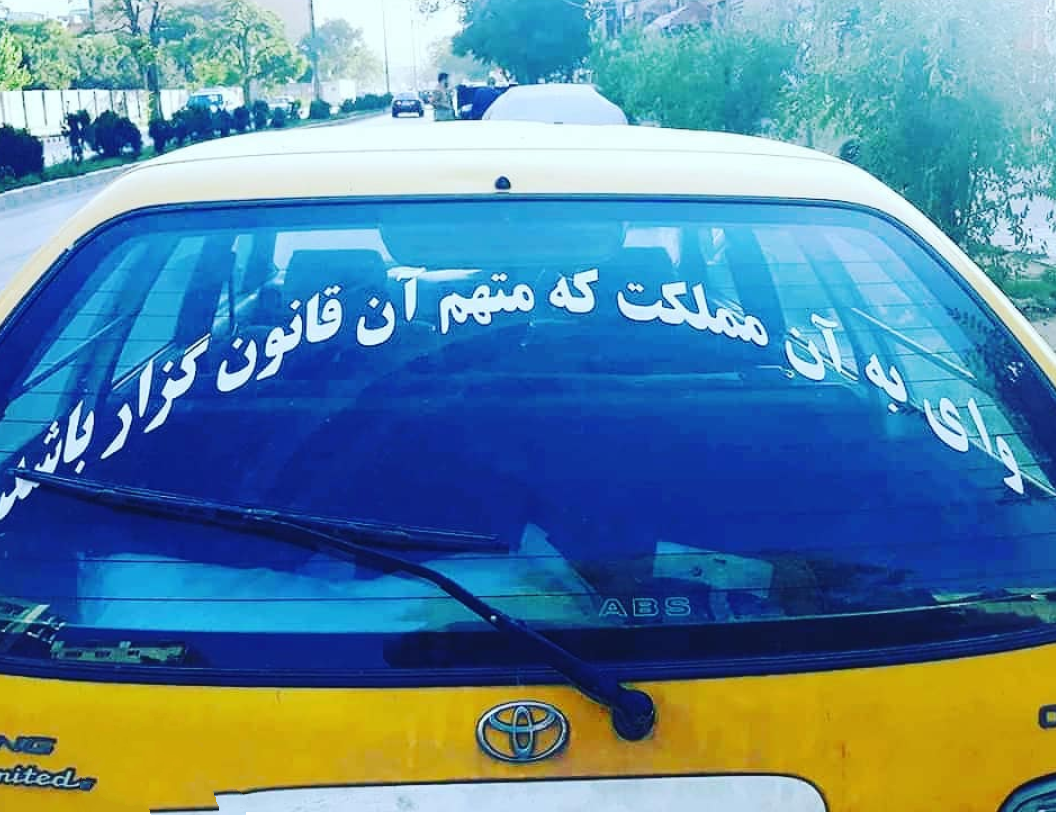

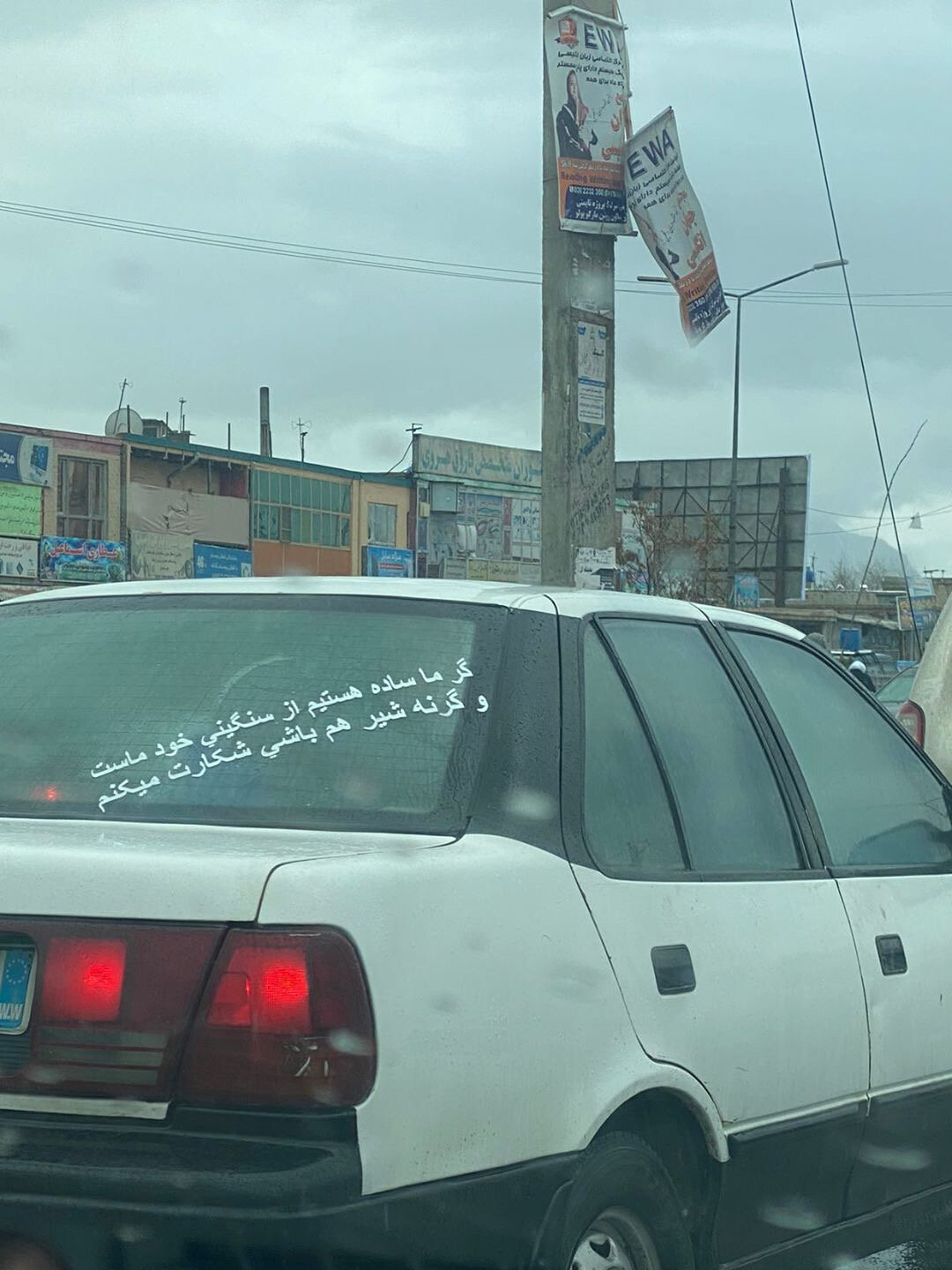

An exponential increase in urban populations coupled with the burgeoning economy of imports in the past two decades is also mirrored in the expansion of cultural expressions. The underprepared infrastructure is nowhere more visible than on the roads. Luckily, to curious eyes even in the customary traffic jams, there are often interesting things to look ahead to. The rear windshields of cars have become passing screens of wisdom, entertainment, and short reads of contemporary life in the city, often bought from car accessory shops or personally commissioned in local printing studios . Though not often taken seriously, these decals are soaked with deep truths about contemporary Kabul’s realities and anxieties.

Figure 1: "We shall go where there is no sorrow." Image by Roya Heydari

In a country entangled in an endless war for over forty years now, the public's faith in humanity has been traded as a commodity by men in search of power. With blind trust and sheer hope for a better future, many have shed blood and tears behind banners and promises that keep growing, only to learn that they have been nothing but the sacrificial lambs for the gains of the small few. The men that fall short of seeing the storm of pain and trauma circling outside their concrete blast walls, drowning the people while they rejoice in their power and wealth. It's no surprise that one would find abundant denouncements of the cowardly friends and the betrayers. Living under a constant shadow of death, one would come to see the end as a light. In the nation's recent celebrated martyrology (ملت شهید پرور), which is evoked by all sides involved in the war, the death of powerful men signals the beginning of their eternal life through images that help both mask their past and guarantee their future presence in the public psyche.

Figure 2: "Shaking hands with cowards is a mistake." Image by Roya Heydari

In a nation whose history is traditionally recalled through the triumphs of kings and warriors, the notion of conquest is reflected today in statements such as "King of the Road." In a history of those in power who have called for people to follow them with blind trust, "Do Not Follow Me" pasted on a car reads like a reminder of their courage and the dawn of a new era. As beyond a self-proclamation of importance, power, and ego, it also serves as a sober reminder that individual life in Afghanistan is a lonely journey, despite the constant sounds of collectivity shouted by the ones in the business of power at the expense of the people there is no side to follow to peace.

Figure 3: "I saw you once, and I went crazy. I went around hundreds of times but didn't fall in love." Image by Muheb Esmat

It's not a secret that "Life is a race" in Afghanistan, which you either compete to win every day or risk being lost like many before. An exhausting game of survival that is left many physical and psychological scars. Amid all these reminders of an existential crisis hovering over the people are also the tender message of love, kindness, and a reminder that "after all, tomorrow is another day." And only tomorrow could tell if it will be a good or bad day.

Figure 4: Image by Muheb Esmat

Figure 5: Image by Atiq Rahimi

In evoking the comparison to poetry, which is a language of illusion and symbolism in the country, I do not seek to create direct lineage but, instead, a connection that sheds light on the history of poetic self-expression in Afghan culture. These moving compositions are odes to a broken society in uncertain times. As the stabilities of life continue to escape the people, their words have become inseparable from the truths around them. In a physically and mentally toxic environment permanently stained with endless conflict and trauma that continues to cut young lives short, the poems have gotten even shorter and potent. Inscribed with social and political realities, these compositions on cars are relics of our time passing in front of our eyes while we look away in search of the grand gestures of expression through institutional venues.

Their appreciation, due credit, and documentation as a legitimate form of self-expression fall victim to the practices of recording cultural and visual histories of the country across rigid lines of modernity (often through a foreign lens) and traditions of the past. These symbolic representations in texts and images taking shape in the most unexpected of places are a product of the people and their culture in conversation with contemporary life in the country. They are signs of a multiplicity of desires and crumbling truths that occupy the hearts and minds of a public divided across linguistic, ethnic, and class lines. Continuous failure in assigning value to a new cultural form–born from contemporary life–further endangers the creation of a fragmented and biased narrative of the nation's visual and cultural history. These compositions pasted on cars are part of a much wider contemporary visual and cultural production in Afghanistan that asks for urgent documentation and critical engagement with.